Introduction

This year's conference was held in Melbourne on the 20th October and in Sydney on the 25th. Summaries from each of the speakers are available on this page. Click on the link below to go to your chosen speaker's summary. Dr Paul Fisher was in Australia as a guest of Climate Alliance.

Dr Paul Fisher (Melbourne and Sydney)

Sarah Barker (Melbourne)

Pauline Vamos (Sydney)

Maged Girgis (Sydney)

Dr Paul Fisher

Dr Fisher was until recently the Deputy Head of the PRA and Executive Director, Supervisory Risk and Regulatory Operations.

Dr Paul Fisher was appointed Deputy Head of the PRA and Executive Director for Supervisory Risk and Regulatory Operations on 1 June 2014. In this role, Dr Fisher was responsible for Supervisory Oversight, Supervisory Support, the PRA Chief Operating Officer and related functions and, through a Director of Specialist Risk Supervision, the PRA Risk Specialists. Dr Fisher was a member of several senior management committees of the Bank and became a PRA Board member on 1 September 2015.

Dr Fisher joined the Bank in 1990, having previously worked at the University of Warwick between 1980 and 1990 where he specialised in research on macroeconomic models and was part of the Bank's senior staff from 1995 until his retirement from the bank in 2016.

Ms Sarah Barker

Sarah has two decades' experience advising Australian and multi-national clients on governance, compliance, misleading disclosure and competition law (antitrust) issues. In addition to tertiary qualifications in commerce and law, she has undertaken postgraduate studies at the London School of Economics, and holds a Masters degree from the University of Melbourne (awarded with Dean's Honours).

Sarah is an experienced director and advisory board member. She is currently a non-executive director of one of Australia's largest superannuation funds, Emergency Services & State Super, and of NRCL Ltd. She has been actively involved as an examiner, lecturer and course materials author for the Australian Institute of Company Directors for more than a decade, including the 'Directors' Duties & Responsibilities' unit of Australia's leading professional directors' qualification, the Company Directors' Course.

Sarah has particular expertise around director and trustee duties, misleading or deceptive disclosures, board governance and effective compliance, and ESG (environmental, social, governance) in investment. Her thought leadership on ESG and fiduciary duties is internationally recognised, with her work on responsible investment receiving awards from organisations such as the Global Corporate Governance Institute and the United Nations PRI. She sits on the Technical Working Group of the international Climate Disclosure Standards Board, and is an academic visitor at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment at Oxford University.

Ms Pauline Vamos

Pauline Vamos was the chief executive officer (CEO) of the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) and has over 25 years’ experience in the financial services industry.

Pauline was CEO of ASFA between 2007 and 2016 and, prior to this, was a senior executive with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). In that role, she managed the implementation of the Managed Investment Act and the Financial Services Reform Act. She has also been a corporate counsel, head of compliance, and strategic risk consultant, as well as a trustee director.

Pauline is a qualified lawyer and previous member of the past Federal Government’s Superannuation Advisory Committee. She was part of the Treasury’s Stronger Super Peak Consultative Group, which was tasked with advising the Government on how to best implement the Stronger Super reforms. Pauline was also a member of the Infrastructure Finance Working Group and the Gillard Government’s Superannuation Roundtable. Pauline was on the Advisory Council for the Centre for International Finance and Regulation (CIFR), an academic centre of excellence for research and education in the financial sector.

Pauline has been voted ‘most influential in the financial services industry’ by Money Management as well as ‘most influential in the superannuation industry’ by Super Review. In 2013, Pauline was recognised as one of the ‘Australian Financial Review and Westpac 100 Women of Influence’. In 2016, Pauline was voted Superannuation Executive Of The Year by Money Management.

Pauline was a member of the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO’s) Superannuation Industry Advisory Group (SIAG), the peak superannuation consultative committee. Pauline is also on the board of the Banking and Finance Oath (BFO) group.

Pauline covered the following points in her talk:

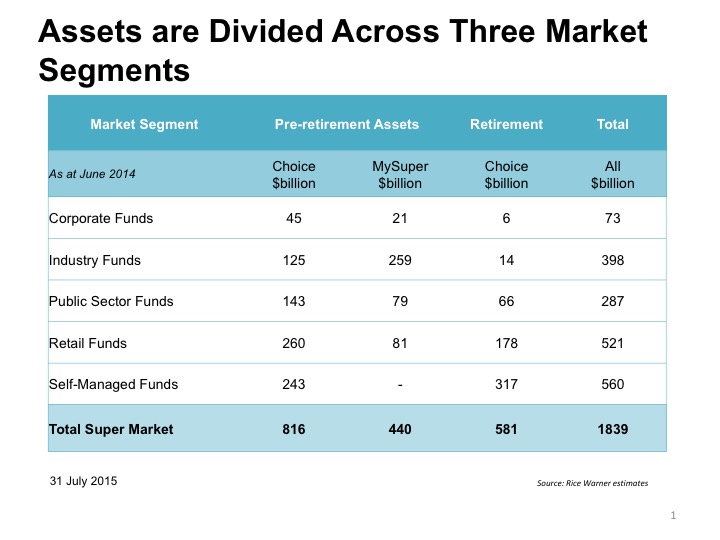

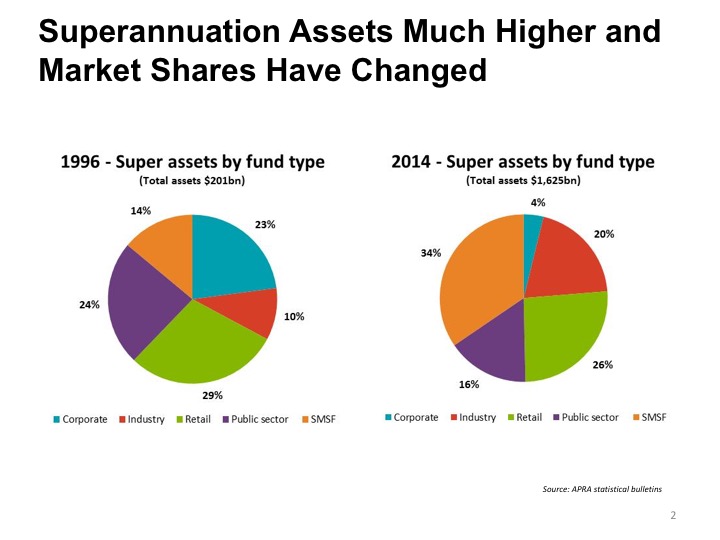

A very brief background of the type of funds and money in the super system as it is not homogenous and this is one of the road blocks to a more industry wide approach to climate change risk.

The relationship between fund managers and super funds and the changing nature of that relationship including the increase in insourcing which means that the larger funds are at least looking at the risk more closely – although there is a lack of in house expertise .

The continuing conflict/confusion some trustees have in relation to ESG considerations and the fact that ESG is still seen as a fringe issue.

The impact of short term performance measures, bias for the banking and mining sector and the poor experience with private equity which limits investment in innovative climate change solutions

The good news - the growing movement by consumers – e.g. No Tobacco – 10 large funds no longer invest, growing class action risk, uni super experience with their members.

↑ Back to top

Mr Mag Girgis

Maged Girgis is one of the country's most respected financial services lawyers with more than 19 years’ experience as a specialist superannuation funds advisor.

Mag advises the full spectrum of financial services industry participants across all legal, regulatory and taxation issues. He acts for corporate, industry, public offer and public sector superannuation funds as well as employers, administrators, trustee companies, life insurers and investment managers.

The main points of Mag's presentation:

Duties

Under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Act), a director of a corporation must exercise their powers and discharge their duties:

with the same care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise in the corporations circumstances if they occupied the office held by that director (s180(1)); and

in good faith in the best interests of the corporation (s181(1)(a)); and

To the extent the company is a superannuation fund, directors are also under a duty to:

exercise, in relation to all matters affecting the RSE, the same degree of care, skill and diligence as a prudent superannuation entity director (ie. professional director) would exercise in relation to a trustee (s52A(2)(b));

perform the director's duties and exercise the trustee's powers in the best interests of the beneficiaries (s52A(2)(c)); and

to exercise a reasonable degree of care and diligence for the purposes of ensuring that the trustee carries out the covenants referred to in section 52 (s52A(2)(f)).

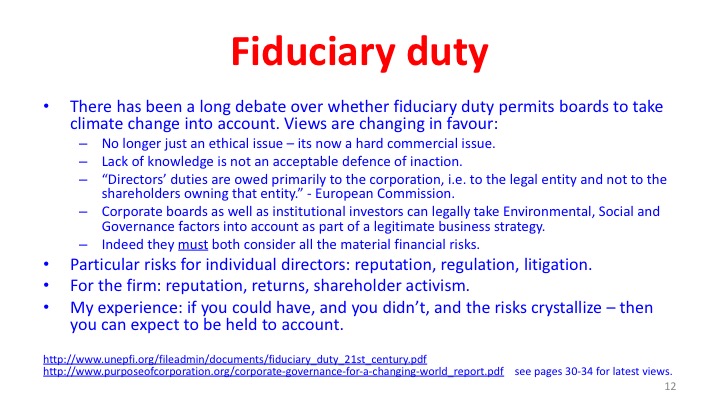

Generally, the best interests of the corporation (and in the case of a superannuation fund, the beneficiaries) are represented by maximising financial performance. As result, it is not for the directors to infuse its own ethical considerations into decisions that it may lawfully make.

Having said this, the interests of the corporation can include the physical, political and regulatory environment in which it operates and so the Courts have held that directors can take these matters into account to the extent that they are linked with the interests of the corporation.

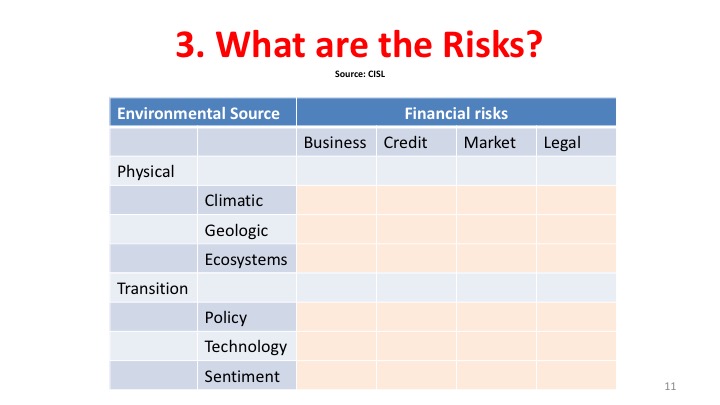

Risks

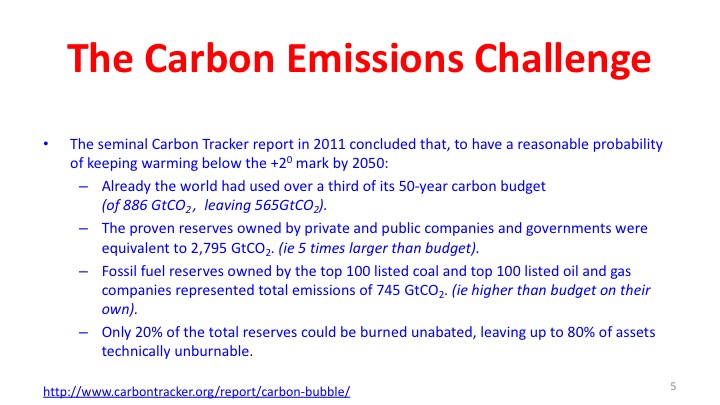

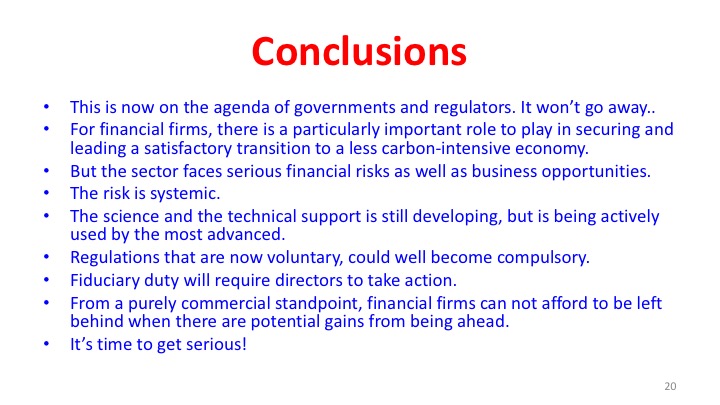

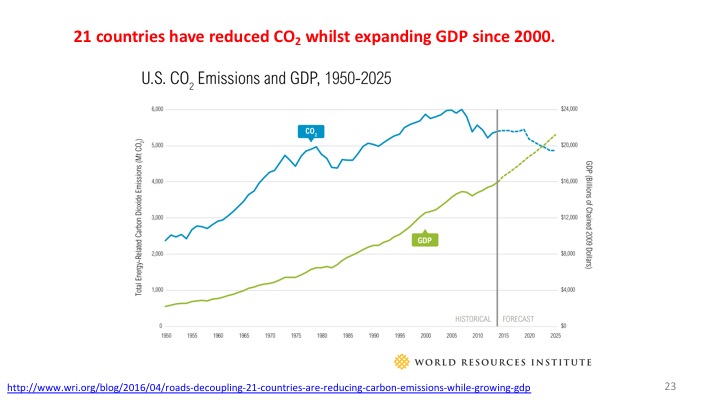

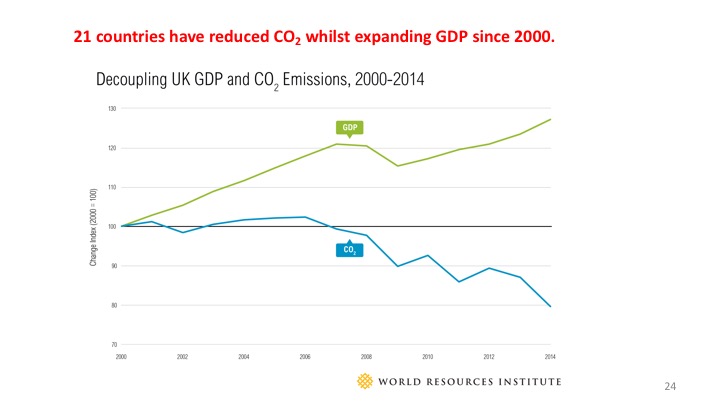

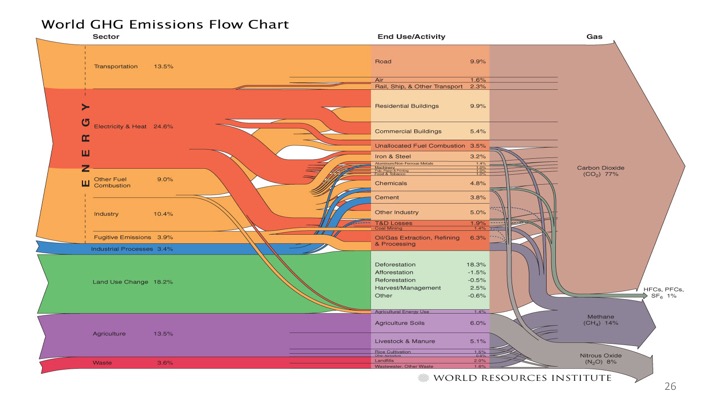

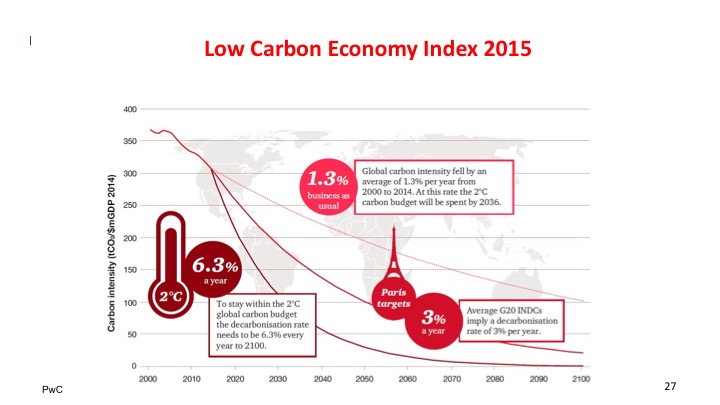

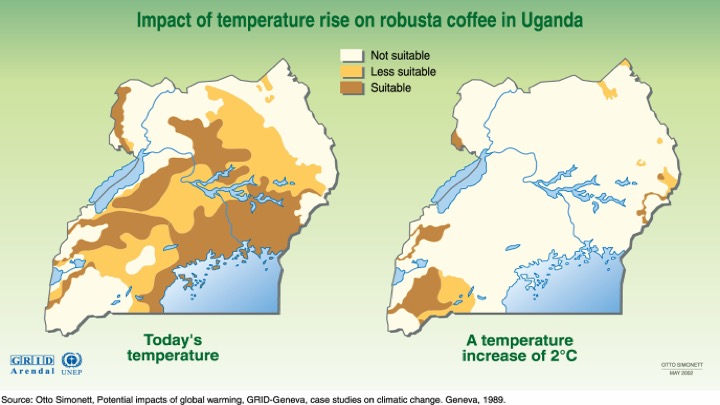

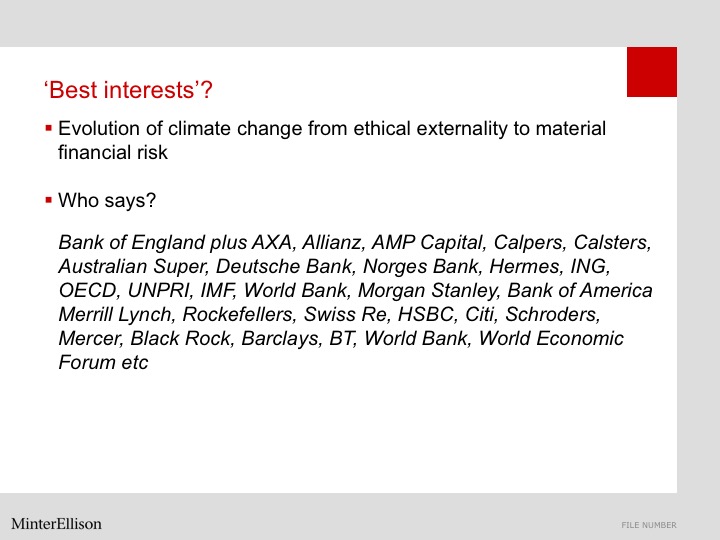

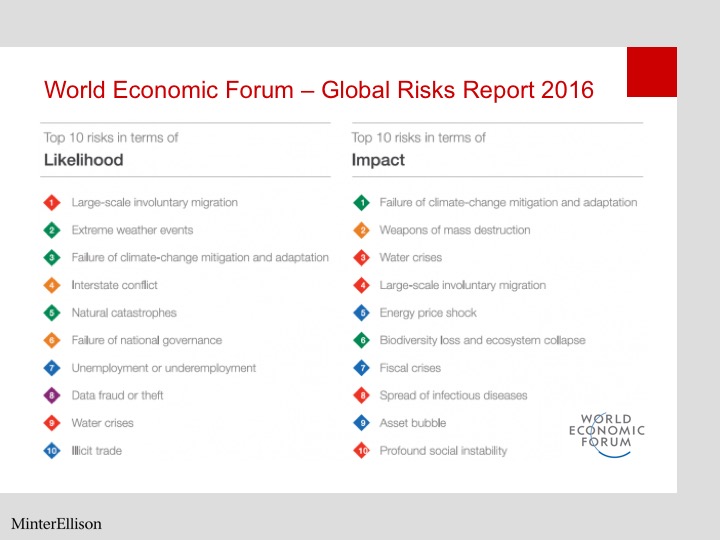

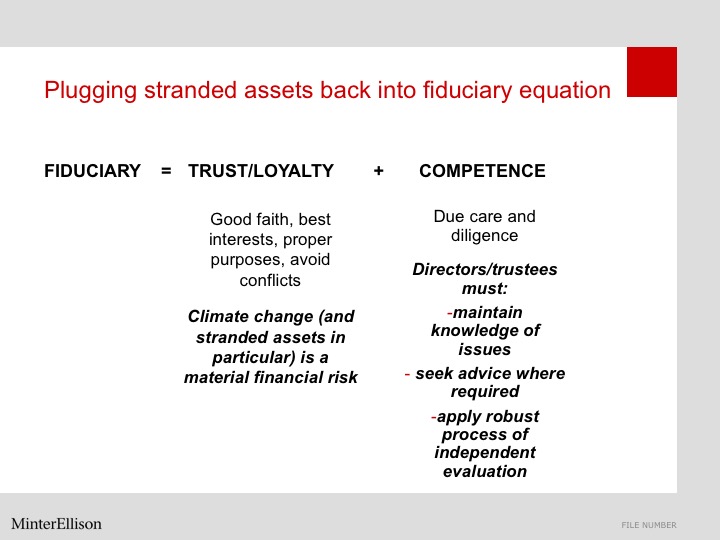

Historically, climate change was often regarded as an ethical issue for investors – a 'non-financial environmental externality' that was secondary to, and largely inconsistent with, the imperative to maximise financial returns. Recently, however, the question of climate change has transformed into one of assessing material financial risk.

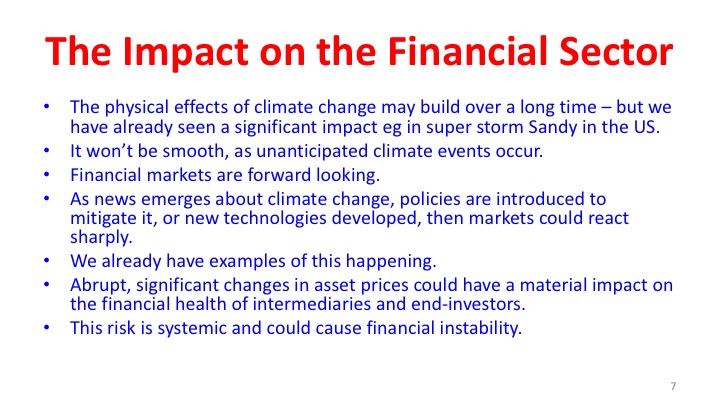

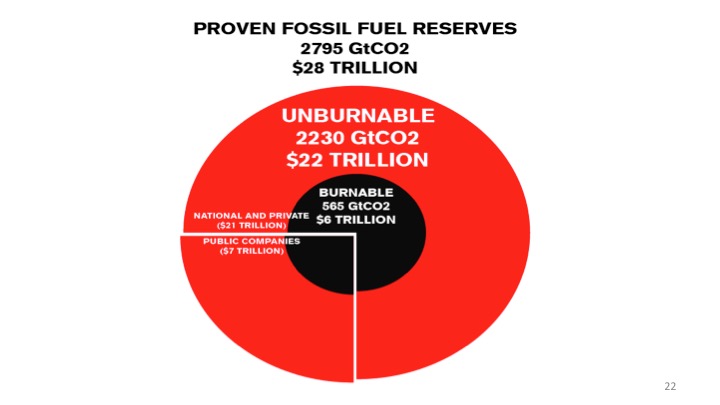

More recently, the financial risks and opportunities presented by climate change have become a mainstream issue for the business community. Debates over 'stranded asset' exposures (eg the IMF, OECD, WorldBank) and asset divestitures play out in the financial press. Recognised economic and financial institutions warn of the significant economic consequences of climate change. And, globally, we are witnessing a surge in political and regulatory interventions in an attempt to deal with climate change and the resulting community concerns.

18 Months ago, special shareholder resolutions were passed at the AGMs of oil giants Shell, BP and Statoil requiring them to stress test their forward strategies against potential climate change futures endorsed by the International Energy Agency. Notably, these resolutions were passed with a resounding majority of 98.3, 99.8 and 99.9% of the shareholder vote, respectively. In each case, less than 3.5% of votes were withheld.

It is important to remember that this is not just from 'ethical' shareholder activists, but also from mainstream institutional investors whose concerns remain squarely centred on risk and return.

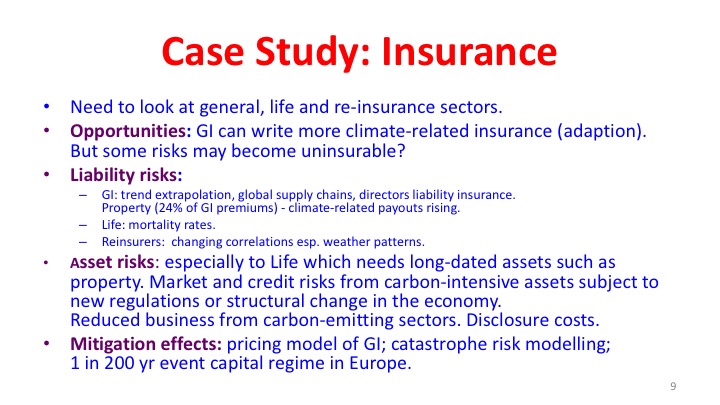

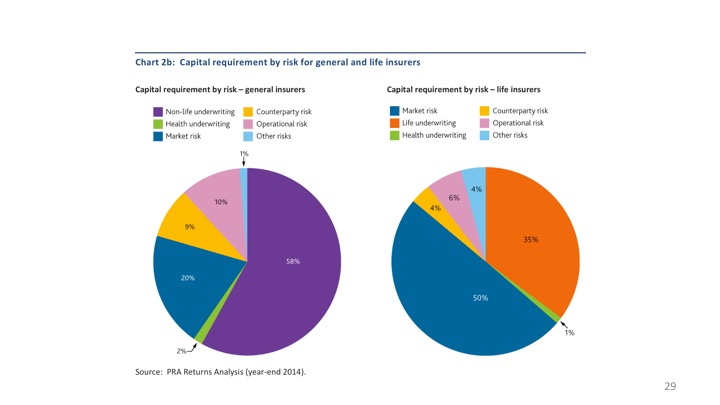

On 29 September 2015, the Bank of England Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) launches its report on The Impact of Climate Change on the UK Insurance Sector (Report).

In the Report, the regulator warns of the significant potential impacts of climate change on both the investment and general underwriting activities of insurers, and on the stability of the financial system more broadly.

The Report identifies three broad channels of systemic risk associated with climate change which 'present a substantial challenge to the business model of insurers'.

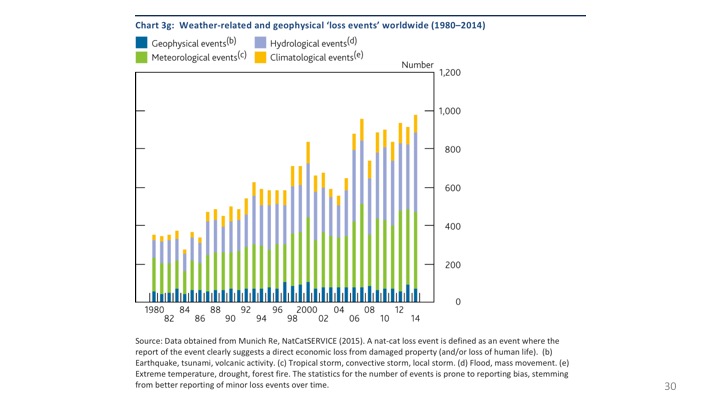

Physical risks - the physical risk of weather related events which most people would ordinarily associate with climate change eg. floods, storms etc.

Transition risks – risks associated with the adjustment towards a lower carbon economy including the rapid re-pricing of carbon-intensive assets and market transformation such as:

stranded asset risk or risk of sudden adverse market movements

community and reputational risk which can quickly and significantly affect investment value (take for example, the speed and impact of the anti-coal seam gas campaign in NSW)

new laws or policy developments that may result in rapid re-pricing of assets (eg. intergovernmental agreements on emissions restrictions)

closure or restriction of markets (eg. the rise in popularity of electric cars and the transformation in the US shoal gas)

technology quickly developing towards lower carbon emissions (eg. developments in battery storage technology, rapid uptake of distributed energy solutions – particularly in emerging markets, rapid uptake of electric vehicles)

relative cost competitiveness between fossil and renewable energy sources

inaccurate business modelling of medium to long term projects (eg. unrealistically low internal price on carbon or failure to factor in the impact of climate change)

maladaptive short-term strategies, ie. investments that may deliver short-term economic gains but exacerbate vulnerability to potential climate change related issues in the medium-long term (eg. locking in capital-intensive infrastructure in a carbon-intensive business, ignoring 'stranded asset' risks)

exploiting opportunities to increase market value across asset classes (eg. active engagement with investee companies around climate change exposures and strategies, recognition of market value perceptions around energy-efficiency for real estate / infrastructure, lower costs of capital and insurance).

Tertiary or liability risks – the risk of increased liability exposure for:

3rd party damage (eg. damage to 3rd parties affected by the company's failure to adapt to climate change risks)

damage to company itself via shareholder derivative action due to cost/loss of value from the failure to adapt); or

to 3rd parties under indemnities or liability policies (eg. professional indemnity and directors’ and officers’ insurance).

These developments illustrate that (irrespective of the view held as to the reality of climate change) market stakeholders view the financial risks (and opportunities) associated with climate change as extending beyond its potential physical risks impacts, to encompass market and legal issues,

Each of these changes can have a relatively quick and significant affect on value and pose both risks and opportunities for corporations.

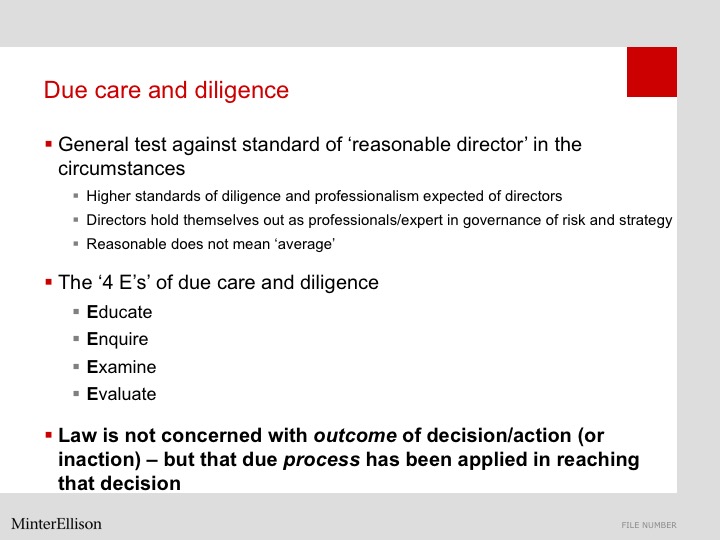

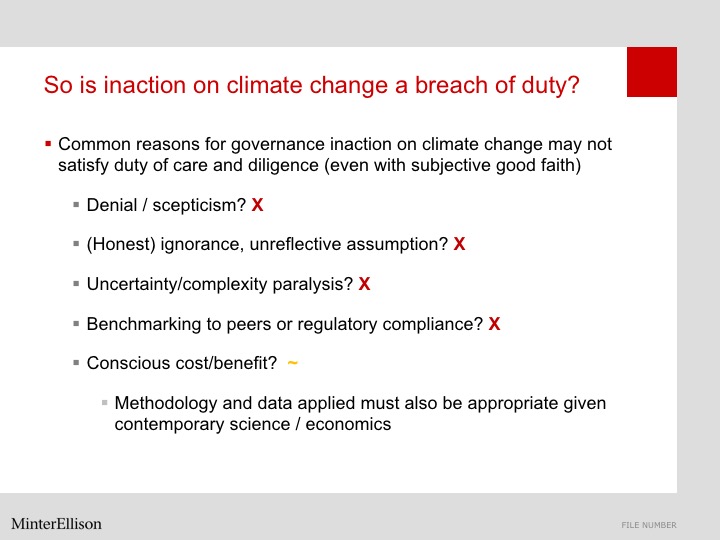

However, that is not to say that companies are duty-bound to decarbonise their investment portfolios, or universally prioritise environmental sustainability or impose their own ethical consideration on the question. The emphasis is not on the outcome of Board deliberations, but on the quality of the information-gathering, the decision making process and the methodologies and assumptions on which those decisions are based.

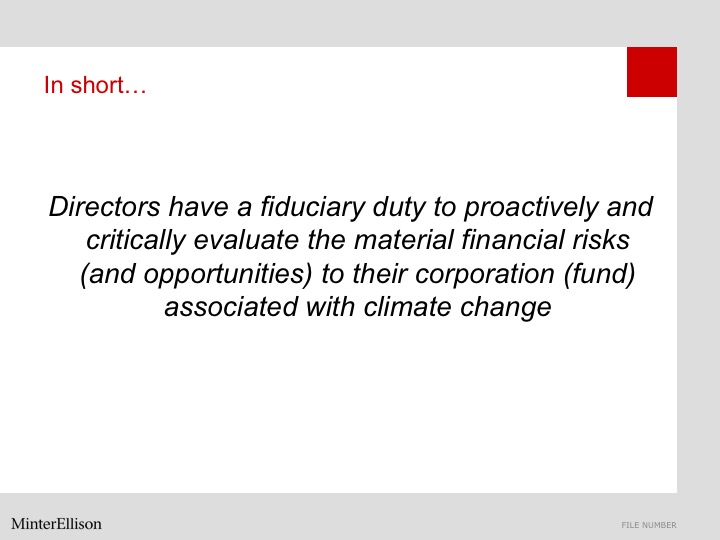

The duty of directors to act in the interest of the corporation and with the requisite duty of care and diligence allows and requires directors to consider the risks and opportunities associated with climate change to the extent that those risks impact on the interests of the corporation.

The degree of care and diligence required of a director in any given context will depend upon the 'nature and extent of the foreseeable risk of harm to the company that would otherwise arise'.

A risk is considered 'foreseeable' if it is not 'far-fetched or fanciful'.[1] Foreseeability should not be confused with probability: a risk that is quite unlikely to occur may nevertheless be foreseeable.

Given the extensive public debate, openly available modelling, the numerous high profile financial institutions and regulators that have warned of the risks and the extensive Government support given to the Paris Agreement internationally, it would be very difficult for any director to argue that climate change risks were not, and could not be, foreseen (irrespective on their personal belief in the science of climate change).

The duty of care and diligence requires a director to obtain knowledge, sufficiently to place themselves in a position to guide and monitor the management of the company. This has been described as a “core, irreducible requirement”.

Recent cases (Centro and James Hardie) have refocussed (arguable sharpened) the duties of individual directors to 'take diligent and intelligent interest in the information available to him or her, to understand that information and apply an enquiring mind to the responsibilities placed upon him or her' (Centro).

As with any other material financial risk, directors will need to skill up, develop and implement a robust process (with appropriate inquiry of independent experts where necessary) in assessing the potential impact of these risks on the company.

Boards need to be aware that these impacts may be both direct and indirect. This means that the Board will need to set process and procedures to ensure that analysis is done. These processes will need to include robust and active consideration of climate change risks based on the methodologies and assumptions that are forward looking.

Directors who conduct this analysis and who act (or decline to act) based upon a rational and informed assessment of the corporation’s best interests, may then have the protection of the 'business judgment rule'.

The 'business judgment rule' protects decisions of directors and officers where the director or officer:

has informed themselves about the subject-matter of the judgment, to the extent they reasonably believe to be appropriate; and

acted in good faith and for a proper purpose, had no material personal interest in the subject matter of the judgment, and

rationally believed “that the judgment is in the best interests of the corporation.”

However, the defence is only available if the director or officer can demonstrate that they informed themselves, made a conscious decision and exercised rational judgment.

Companies must also ensure that their practice continues to accurately reflect its stated beliefs, objectives and public commitments (eg ESG policy).

Shaping litigation

Traditionally the focus of causes of action of climate change litigation has been on ‘failure to mitigate’. Eg. the Illinois Farmers Insurance v The Metroplitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (2014) for failing to mitigate the effects of climate change on stormwater runoff systems.

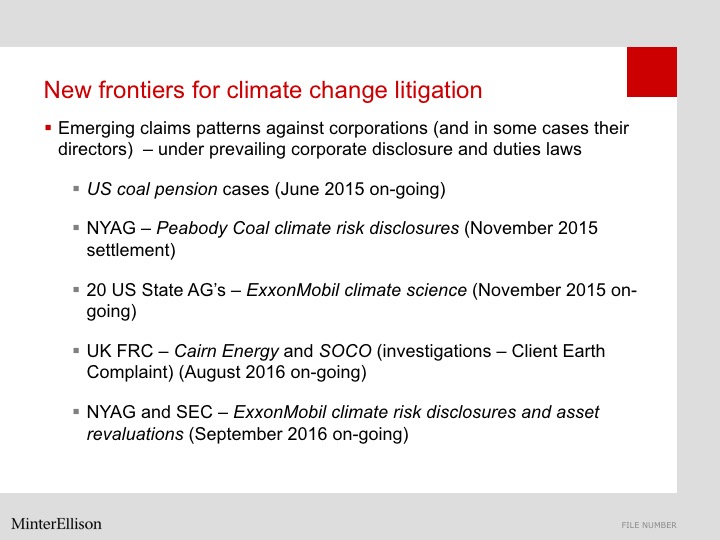

However, there are emerging patterns in claims using prevailing corporate, securities and tort laws. Claims are now more akin to ‘failure to adapt’.

Pension cases: Recently, members of the Arch Coal pension plan filed proceedings in the US District Court against Plan fiduciaries seeking compensation for a drop in the value of pension funds invested in company stock, which is alleged to have plummeted in value by 96% over the three and a half-year claim period due to the structural decline in coal. A similar action has been started against another pension fund along similar lines.

Misleading and deceptive conduct: Within the last year, the NY Attorney General has taken regulatory action against one of the largest US coal companies on the grounds that it engaged in false and misleading conduct in connection with securities transactions in understated the financial risks posed to the company by climate change.

Other potential causes of action: Climate & Pensions Legal Initiative (Client Earth / AODP) (foreshadowed 2015)

Regulators

Through IOSCO and other forums, Australian regulators (such as ASIC and APRA) are becoming more and more interested in this space, influenced by overseas thinking. While not imminent, it is not far fetched to imagine Australian regulators issuing guidance, prudential standard or even capital standards at some point in the future.

[1] Council of the Shire of Wyong v Shirt (1980) 146 CLR 40 at 47-48 per Mason J; ASIC v Rich (2009) 75 ACSR 1 at 621 [7231] per Austin J.